By Linda Ballou, NABBW’s Adventure Travel Associate

On my visit to South Africa in 2015, I was surprised to learn that there are too many elephants! With so many environmental groups fighting to prevent the poaching of these emblematic creatures for their ivory tusks, it was ironic to learn that as early as five years ago, the African parks were actually dealing with elephant over-population. Then, an estimated 120,000 elephants roamed the vast, unfenced preserves of Botswana under the protection of armed, patrolling rangers. Today there are 130,000.

But that’s just the Botswana elephant population. Add in neighboring Namibia, Zimbabwe and South Africa and the African elephant headcount is estimated at 256,000, or more than half of the total estimated elephant population of Africa.

In response to the growing population Mokgweetsi Masisi, the President of Botswana, lifted the ban on hunting elephants set in place in 2014. Conservationists who have been working for years to find a better answer to the problem are infuriated.

Why Is the Growth of the African Elephant Population a Problem?

Elephants graze about 18 hours a day, each taking in about 400 pounds of grasses that the kudu, impala, sable, and other wildlife need to survive. They eat the leaves of the Mopane tree that giraffes and other creatures rely upon.

Dead zones are left in their wake where they have eaten everything down to a nub and killed trees by debarking them with their tusks. This rate of unsustainable devastation will leave animals starving if something is not done to curb damage caused by the growing population of elephants clustered in Southern Africa.

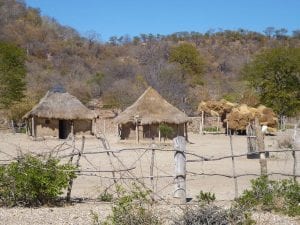

Michael Masukule, leader of a community adjacent to Kruger National Park in South Africa, said, “They destroy our crops, occupy our drinking places, compete with our livestock for food, and are a danger to our people. Whatever decision you take, do not forget us people who encounter elephants every day.“

Villagers live in fear of the pachyderms that plunder their crops at night leaving them without enough food for winter. Elephants have killed people living on the edge of and inside national parks when they’ve tried to stop them from eating everything in sight.

Villagers live in fear of the pachyderms that plunder their crops at night leaving them without enough food for winter. Elephants have killed people living on the edge of and inside national parks when they’ve tried to stop them from eating everything in sight.

On the flight from Chobe, Botswana to Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, we gazed upon a seemingly endless green carpet of Mopane forests pocked with the watering holes of thousands of resident elephants. It was hard to believe that there is not enough space to go around. But since 80 percent of Botswana is desert, the remaining 20 percent must be shared by vast herds of zebra, antelope, and elephants – and roughly 2.3 million humans.

Are There Any Viable Solutions to This Elephant Overpopulation?

Several solutions have been suggested, including:

- Introducing birth control, which has proven to be both too expensive and impractical as the drug has to be re-injected every six months to be effective.

- Culling the herds is talked about in whispers, but government officials are afraid that approach will alienate visitors and might even trigger economic sanctions from other countries who are not living with the elephants devastation, and do not understand the gravity of the situation.

Culling is particularly problematic because of the legendary intelligence and memory of the elephants. If they see humans killing off family members, they are likely to become aggressive and more dangerous to villagers and tourists alike. The entire family, including babies, would have to be killed at the same time to prevent this type of revenge. It’s not feasible.

- Installing hives of African bees. There are, however, some smaller steps that can be taken to minimize the effects of elephants on local crops. Elephants are afraid of bees. The installation of hives of African bees at intervals surrounding a field have effectively deterred the elephants and given the villagers income from the honey they produce.

In 2002, researchers found that African elephants stay away from acacia trees with beehives. Later studies revealed that not only do the elephants run away from the sound of buzzing bees, they also emit low-frequency alarm calls to alert family members about the possible threat.

- Planting a buffering crop of chilies. Just as they don’t like bees, elephants don’t like chilies. Capsaicin, the chemical in chilies that make them hot, is an irritant causing elephants to cough, sneeze, and eventually turn away from crops surrounded by a buffer of chilies. (For more details on this plan, refer to the 2014 BBC article by Shreya Dasgupta.)

- KAZA – or migrating the elephants elsewhere. Other solutions considered are extending existing parks through more land acquisitions, moving more elephants from overpopulated to underpopulated parks, and opening corridors between parks to allow elephants to resume some of their old migration routes. Enter the Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area also known as KAZA TFCA – which opens up elephant migration routes crossing international borders.

This initiative of the governments of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe was formulated in 2012. It involves the land situated in the Okavango and Zambezi river basins where the borders of the five countries converge.

Sadly, implementing the good intentions of this agreement has proven to be difficult, as the elephants are not co-operating. They are remaining clustered in parks like Hwange in Zimbabwe where there are man-made watering holes able to sustain them throughout the dry season.

“KAZA is a wonderful idea whose success will be determined in decades rather than years. This region is a very dry region with and has limited water resources. The elephant is a water-dependent species. Getting elephants to move (migrate) may very well be impossible as they follow the memories of the matriarch(s) who may have never learned a migratory pattern.

“KAZA is a wonderful idea whose success will be determined in decades rather than years. This region is a very dry region with and has limited water resources. The elephant is a water-dependent species. Getting elephants to move (migrate) may very well be impossible as they follow the memories of the matriarch(s) who may have never learned a migratory pattern.

“Just because KAZA is implemented doesn’t mean the elephants can take advantage of it. They are at the mercy of the elements and their needs. Shutting down the man-made resources might stimulate elephant movement, but it will also cause tourism to suffer, one of the main reasons for the treaty being created,” according to Mat Dry, Safari Guide, author of This is Africa, and owner of TIA Safaris.

This article is not designed to diminish or minimize the efforts of conservationists fighting to prevent the slaughter of elephants in the Congo by militants who sell the ivory to purchase ammunitions, or in the Selous in Tanzania, a park that has been ravaged by poachers. That horrendous disregard for life must stop.

However, Africa is an enormous continent and what is true in the Congo and other parts of Africa is not the reality in other countries. Outsiders should understand that if culling becomes the only answer to this problem, it will not happen until all else fails.

However, Africa is an enormous continent and what is true in the Congo and other parts of Africa is not the reality in other countries. Outsiders should understand that if culling becomes the only answer to this problem, it will not happen until all else fails.

But, again, this current situation is not sustainable for the other animals in the parks or for the humans living in and/or on the edge of the last great wild places in Africa.

Sadly, instead of ordering culling in a responsible, humane way by rangers, the elephants are to be shot by trophy hunters. Elephants are intelligent creatures with keen memories who protect members of their family.

This approach of killing a single adult member of a family will create angry, vengeful matriarchs, and rogue bulls that will likely terrorize villagers. When I was in Zimbabwe, I could hear the low rumble of the elephants grazing peacefully nearby our tent camp while we were sleeping. A marauding elephant could easily destroy a wilderness camp. This is a dangerous response to a serious problem that could wreak havoc for the 2-billion tourist industry.

The restriction of flights to Africa to prevent the spread of COVID-19 is giving elephants a reprieve. Hunters can’t enter the country, but, according to a recent Bloomberg.com article by Antony Squazzin, “Seven hunting packages, of 10 elephants each, were available for auction. Only one (package) was not sold as no bidders met the reserve price of 2 million pula ($181,000),” said Adrian Rass, managing director of Auction It Ltd, of Botswana.

The restriction of flights to Africa to prevent the spread of COVID-19 is giving elephants a reprieve. Hunters can’t enter the country, but, according to a recent Bloomberg.com article by Antony Squazzin, “Seven hunting packages, of 10 elephants each, were available for auction. Only one (package) was not sold as no bidders met the reserve price of 2 million pula ($181,000),” said Adrian Rass, managing director of Auction It Ltd, of Botswana.

Hopefully, an answer to the elephant conundrum will appear by the time things get back to our “new normal.”

Note: Special thanks to photographer Tom Schwab for the wonderful elephant photos.

This article first published on the National Association of Baby Boomer Women,

Editor: Anne Holmes, Boomer CEO

Linda Ballou is an adventure travel writer with a host of travel articles on her site www.LostAngelAdventures.com. You will also find information about her travel memoir, Lost Angel Walkabout-One Traveler’s Tales from Alaska to New Zealand, and Lost Angel in Paradise where she shares her favorite hikes and day trips on the coast of California.

Subscribe to her blog www.LindaBallouTalkingtoYou.com to receive updates on her books, travel destinations and events.

No comments:

Post a Comment